THE BLACK ASSEMBLY

David G. Roebuck

IN MAY 1909, Bahamian-born Edmond Barr and his American-born wife, Rebecca, joined the Church of God during A.J. Tomlinson’s ministry at the Pleasant Grove Camp Meeting in Durant, Florida. Since that providential encounter, individuals of African descent have participated in the global ministry of the Church of God. Our more than 7 million members include racial and ethnic diversity among adherents residing around the world.

General Overseer Tomlinson often encouraged the development and inclusion of people of color in the Church of God. His grandparents and father had helped slaves escape bondage by way of the Underground Railroad in Indiana and were staunch abolitionists. Tomlinson recognized the significance of the ministry of African-American William J. Seymour, who was pastor of the famous Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles, and Tomlinson likely interacted with Charles H. Mason, founder of the Church Of God In Christ.

Many of the details concerning our earliest black congregations have not yet been recovered. The Barrs traveled to the Bahamas in November 1909 and were instrumental in establishing several congregations there. Then in 1911, they organized a congregation in Miami where there was a large population of Bahamian immigrants. One of their companions, Sampson Ellis Everett, may have begun ministering in Jacksonville as early as 1909, which led to establishing a congregation in Florida’s largest city. By the end of 1912, there were also black congregations in Coconut Grove and Webster, Florida, according to the Minutes of the January 1913 General Assembly.

On June 4, 1912, Tomlinson recorded in his journal: “Held a conference meeting yesterday to consider the question of ordaining Edmond Barr (colored) and setting the colored people off to work among themselves on account of the race prejudice in the South.” Ordination authorized Barr to establish churches and grant ministerial credentials. In 1915, Tomlinson appointed Barr as overseer of the black churches in Florida. The next two years saw an increase from seven to thirteen black churches and from 111 to 200 members. For several reasons, Tomlinson did not reappoint Barr as an overseer in 1917, and from then until 1922, black churches served under the same jurisdiction as white congregations.

Tomlinson’s 1912 journal entry regarding “race prejudice in the South” acknowledged the deep racial divide that existed into the second half of the twentieth century. During a time of tremendous hardship for Black Americans, the evils of segregation led to separate and very unequal opportunities. Jim Crow laws excluded Black Americans from using many public businesses and facilities, and made it difficult to function in general society. Their being denied access to many motels, restaurants, and restrooms created ministry challenges, especially when black bivocational pastors often had to drive long distances to serve their congregations. To add to the injustice, ignoring these laws could result in beatings, incarceration, and even lynching.

Church of God members were not exempt from these harsh laws and customs, which remained in effect until the 1960s. Although black members were welcome at all Church of God General Assemblies, civil law required them to sit in sections designated for “colored” attendees. This was even true when the General Assembly met in the Assembly Auditorium in Cleveland, Tennessee. Although these laws and customs often made it more practical for people of African descent to join predominantly black denominations, many remained in the Church of God because of their commitment to our government and theology, as well as the relationships and fellowship they experienced.

General Overseer Tomlinson often encouraged the development and inclusion of people of color in the Church of God. His grandparents and father had helped slaves escape bondage by way of the Underground Railroad in Indiana and were staunch abolitionists. Tomlinson recognized the significance of the ministry of African-American William J. Seymour, who was pastor of the famous Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles, and Tomlinson likely interacted with Charles H. Mason, founder of the Church Of God In Christ.

Many of the details concerning our earliest black congregations have not yet been recovered. The Barrs traveled to the Bahamas in November 1909 and were instrumental in establishing several congregations there. Then in 1911, they organized a congregation in Miami where there was a large population of Bahamian immigrants. One of their companions, Sampson Ellis Everett, may have begun ministering in Jacksonville as early as 1909, which led to establishing a congregation in Florida’s largest city. By the end of 1912, there were also black congregations in Coconut Grove and Webster, Florida, according to the Minutes of the January 1913 General Assembly.

On June 4, 1912, Tomlinson recorded in his journal: “Held a conference meeting yesterday to consider the question of ordaining Edmond Barr (colored) and setting the colored people off to work among themselves on account of the race prejudice in the South.” Ordination authorized Barr to establish churches and grant ministerial credentials. In 1915, Tomlinson appointed Barr as overseer of the black churches in Florida. The next two years saw an increase from seven to thirteen black churches and from 111 to 200 members. For several reasons, Tomlinson did not reappoint Barr as an overseer in 1917, and from then until 1922, black churches served under the same jurisdiction as white congregations.

Tomlinson’s 1912 journal entry regarding “race prejudice in the South” acknowledged the deep racial divide that existed into the second half of the twentieth century. During a time of tremendous hardship for Black Americans, the evils of segregation led to separate and very unequal opportunities. Jim Crow laws excluded Black Americans from using many public businesses and facilities, and made it difficult to function in general society. Their being denied access to many motels, restaurants, and restrooms created ministry challenges, especially when black bivocational pastors often had to drive long distances to serve their congregations. To add to the injustice, ignoring these laws could result in beatings, incarceration, and even lynching.

Church of God members were not exempt from these harsh laws and customs, which remained in effect until the 1960s. Although black members were welcome at all Church of God General Assemblies, civil law required them to sit in sections designated for “colored” attendees. This was even true when the General Assembly met in the Assembly Auditorium in Cleveland, Tennessee. Although these laws and customs often made it more practical for people of African descent to join predominantly black denominations, many remained in the Church of God because of their commitment to our government and theology, as well as the relationships and fellowship they experienced.

|

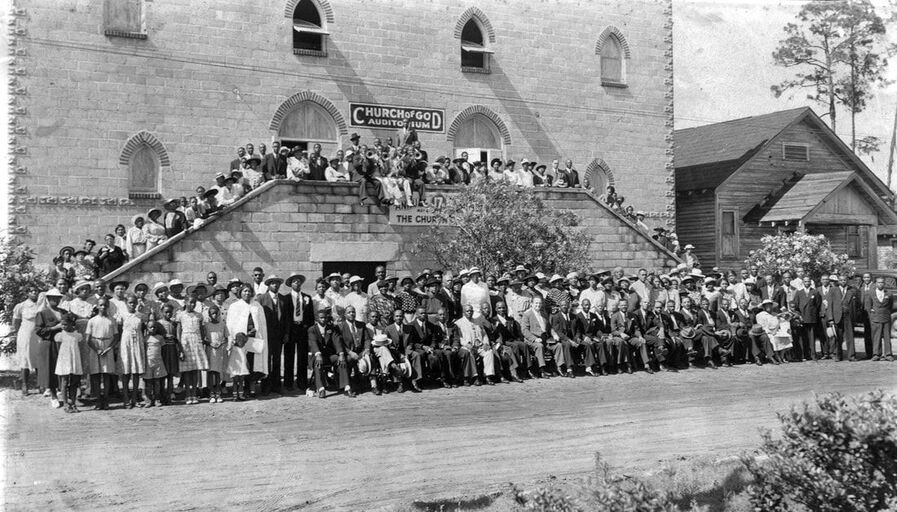

“Church of God (Colored Work)”

Even with their loyalty to the Church of God, because of the challenges of interracial meetings, back members requested a separate overseer and structure. Tomlinson acknowledged the request at the 1922 General Assembly: “I feel that the time has come that some mention should be made about our colored people. There is a problem confronting us that is yet to be solved. South of the Mason and Dixon line it is difficult to show them all the courtesy that we would like to. It is our purpose to make them feel at home with us and they do in a sense, but on account of conditions that seem to be unalterable a number of them are going away from us each year. They are joining with an organization of colored people. They say they love the Church of God and would love to remain, but under the circumstances they feel better to be in a church to themselves where they can be perfectly free in every respect” (A. 1922, p. 25). In an effort to make it more conducive for black members to remain in the Church of God, the General Assembly agreed to appoint a black overseer over black churches. The Executive Committee then appointed Thomas J. Richardson as overseer of black churches. By this time, there were black churches in Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. Challenges remained for the advancement of black ministries in the Church, however. In 1926, black ministers made a recommendation for the Assembly to find a way to “better take care of our affairs among the colored work.” In response, the General Assembly agreed that . . . “The colored people be allowed to have a colored Assembly and they still are and shall be recognized as the Church of God, and that we all belong to the body of Jesus (the Church of God). Neither shall it be construed that they are a body separate and apart from the General Annual Assembly of the Churches of God, therefore the General Secretary and Treasurer shall have charge of their tithes to be used exclusively for them” (A. 1926, p. 38). Over the next four decades, black churches developed a separate structure referred to as the “Church of God (Colored Work).” These congregations created a national office in Jacksonville, Florida, where they built the Church of God Auditorium for Annual Assemblies, as well as a place of worship for a local congregation. The “Church of God (Colored Work)” encouraged the emergence and ministry of black leadership, provided opportunities for support and fellowship at a time when Southern laws excluded Black Americans from many of the public social events of the day, and fostered a sense of common identity among black members and ministers. Through the work of their Annual Assembly, black churches established a Bishops Council, Board of General Trustees, Sunday School and Young People’s Missionary Board, Burial Auxiliary, Disabled Ministers Fund, National Youth Congress, and quarterly Union Meetings. They appointed state overseers, evangelists, and missionaries to various states, adopted a funding strategy for developing new field works, and established a publication known as the Church of God Gospel Herald. Following Thomas Richardson, national overseers included David LaFleur (1923–1928), J.H. Curry (1928–1939), N.S. Marcelle (1939–1946), W.L. Ford (1946–1950 and 1954–1958), and George A. Wallace (1950–1954). Beginning in 1958, the Church of God appointed white overseers to supervise the “Church of God (Colored Work).” J.T. Roberts served as national overseer from 1958 to 1965, and David Lemons served from 1965 to 1966. In 1926 the Black Assembly purchased property in Eustis, Florida, for an industrial school and orphanage. Women were placed in administration over the school and orphanage in 1927. Jessie L. Hayward served as the general president from 1929 to 1938, and she raised funds by visiting black congregations. The first two-story building served as the girls’ dormitory and a classroom. Later a second building was built to house the dining room and kitchen. The boys’ dormitory was constructed under Melissa Marcelle’s administration (1940–1946), and included an auditorium on the first floor. Mrs. Shirley Wallace organized the National Black Ladies Ministries in 1952 and served as teacher and principal of the school and orphanage. |

RESOLUTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

WHEREAS, The gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ is relevant to the problem of human rights; and, WHEREAS, The issue of human rights focuses upon the integrity of our democracy; and, WHEREAS, That Christian obedience to the Law of Love requires a concern for one’s neighbor is plainly enjoined in Scripture; and, WHEREAS, No Christian can manifest a passive attitude when the rights of others are jeopardized; BE IT RESOLVED, That the Church of God continue to create a climate of informed and spiritual opinion; and, BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, That we identify a basic premise on which concerned opinion must rest. That premise, undergirded by the dignity and worth of every individual, assures all Americans the right to full citizenship. In particular this means that no American should, because of his race, or religion, be deprived of his right to worship, vote, rest, eat, sleep, be educated, live, and work on the same basis as other citizens; and, BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, That Christian love and tolerance are incompatible with race prejudice and hatred; and, BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, That the Church of God—recognizing that moral problems are ultimately solved by changing the heart of the individual by the power of the Holy Ghost, resulting in a love for all men—supports that which assures all people those freedoms guaranteed in our Constitution; and, BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, That the Church be urged to continue to practice the love and brotherhood it preached. Minutes of the 50th General Assembly of the Church of God (1964) |

|

|

Integration

The 1960s brought changes in race relations and civil rights throughout the United States. The Church of God responded with a move toward integration. The General Assembly passed a resolution on Human Rights in 1964 and dissolved the separate “Church of God (Colored Work)” in 1966. Because of the large number of black churches in Florida, ministers there asked the Executive Committee to appoint a black overseer for black churches in that state—in effect, returning to the days of Edmond Barr with both white and black overseers.

Although the national meetings ended with racial integration in 1966, the Church of God Auditorium in Jacksonville served as the Florida State Office for black churches until they purchased a new office in Cocoa in 1978. The local congregation continued to worship in the Church of God Auditorium. Surrounded by an aging neighborhood, there was no room to expand, however. Bishop Thomas Chenault led the congregation to locate property at 5755 Soutle Drive, and Bishop Percell Sanders organized fund-raising and broke ground at the new property in 1986. Known today as the Church of God Sanctuary of Praise, Bishop Wallace J. Sibley Jr. dedicated their current facilities on June 13, 1991.

The 1960s brought changes in race relations and civil rights throughout the United States. The Church of God responded with a move toward integration. The General Assembly passed a resolution on Human Rights in 1964 and dissolved the separate “Church of God (Colored Work)” in 1966. Because of the large number of black churches in Florida, ministers there asked the Executive Committee to appoint a black overseer for black churches in that state—in effect, returning to the days of Edmond Barr with both white and black overseers.

Although the national meetings ended with racial integration in 1966, the Church of God Auditorium in Jacksonville served as the Florida State Office for black churches until they purchased a new office in Cocoa in 1978. The local congregation continued to worship in the Church of God Auditorium. Surrounded by an aging neighborhood, there was no room to expand, however. Bishop Thomas Chenault led the congregation to locate property at 5755 Soutle Drive, and Bishop Percell Sanders organized fund-raising and broke ground at the new property in 1986. Known today as the Church of God Sanctuary of Praise, Bishop Wallace J. Sibley Jr. dedicated their current facilities on June 13, 1991.

SHOUTING IN THE SECOND STORY

“On entering the auditorium Sister Emma Barr was the first to dance upstairs. . . .”

“On entering the auditorium Sister Emma Barr was the first to dance upstairs. . . .”

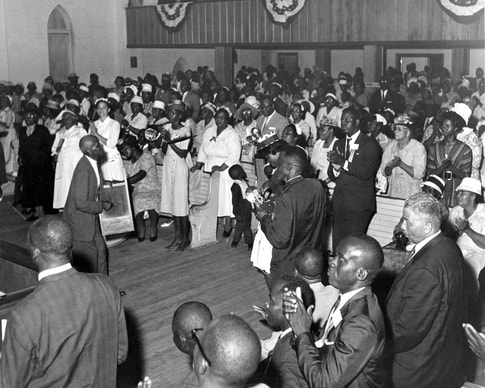

Worship at a Black Assembly in Jacksonville

Worship at a Black Assembly in Jacksonville

Sunday, April 12, 1936, was no ordinary day for the “saints” gathering in Jacksonville, Florida. It was the first day of the Annual Assembly of the Church of God’s black constituency. And it was a day of celebration as members and ministers dedicated the second floor of the Church of God Auditorium located at the corner of Steele and Blue Streets. Their celebration included marching, singing, preaching, shouting, and dancing.

Although the basement of the Church of God Auditorium had been available since their 1932 Assembly, the sanctuary on the second level was not ready for use until 1936. Erected in the middle of the Great Depression with the love and sacrifice of many people, the building was constructed for $18,000 and valued at $25,000. C.F. Bright, who was an experienced builder and served as both the local pastor and state overseer of black churches in Georgia and North Carolina, oversaw the construction. Not surprisingly, women’s groups were recruited to help raise construction money.

Fund-raising efforts included pledges, special offerings, and coupon redemption. Each member was asked to donate not less than one dollar, and there was an ongoing campaign to redeem Octagon soap coupons. Colgate produced Octagon soap for the laundry, but many people used it as an all-purpose soap. In order to promote the sale of individual bars, the soap’s wrapper included a coupon that could be redeemed for cash or merchandise. Between June 1931 and December 1935, members redeemed 205,862 coupons for $886.81.

Their sacrifice and hard work turned into joyous celebration on dedication day, however. The record of events that day includes singing and preaching, as well as a baptismal service. Assembly delegates circled both the old and new buildings and read Psalm 121. They then marched to the new auditorium singing “Moving Higher.” Joy and praise filled the air as they entered and worshiped in the new facilities. Past and present church leaders, as well as community representatives, participated. W.L. Ford later reported to the Church of God Evangel, “Our dedicatory service was very impressive, after which we felt that the second story was God’s house. We were happy to shout in the second story this year.”

Although the basement of the Church of God Auditorium had been available since their 1932 Assembly, the sanctuary on the second level was not ready for use until 1936. Erected in the middle of the Great Depression with the love and sacrifice of many people, the building was constructed for $18,000 and valued at $25,000. C.F. Bright, who was an experienced builder and served as both the local pastor and state overseer of black churches in Georgia and North Carolina, oversaw the construction. Not surprisingly, women’s groups were recruited to help raise construction money.

Fund-raising efforts included pledges, special offerings, and coupon redemption. Each member was asked to donate not less than one dollar, and there was an ongoing campaign to redeem Octagon soap coupons. Colgate produced Octagon soap for the laundry, but many people used it as an all-purpose soap. In order to promote the sale of individual bars, the soap’s wrapper included a coupon that could be redeemed for cash or merchandise. Between June 1931 and December 1935, members redeemed 205,862 coupons for $886.81.

Their sacrifice and hard work turned into joyous celebration on dedication day, however. The record of events that day includes singing and preaching, as well as a baptismal service. Assembly delegates circled both the old and new buildings and read Psalm 121. They then marched to the new auditorium singing “Moving Higher.” Joy and praise filled the air as they entered and worshiped in the new facilities. Past and present church leaders, as well as community representatives, participated. W.L. Ford later reported to the Church of God Evangel, “Our dedicatory service was very impressive, after which we felt that the second story was God’s house. We were happy to shout in the second story this year.”

David G. Roebuck, Ph.D. is director of the Dixon Pentecostal Research Center, Church of God Historian,

and Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity at Lee University.

and Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity at Lee University.