THE NEW TESTAMENT PATTERN

David G. Roebuck

THE COMMITMENT to follow a biblical pattern of Church government has shaped the Church of God from our founding in 1886. R.G. Spurling called for Christian Union members to “take the New Testament, or law of Christ, as your only rule of faith and practice.” His invitation was to give “each other equal rights and privilege to read and interpret for yourselves as your conscience may dictate” and to sit “together as the Church of God to transact business [as] the same…” (Tomlinson, Last Great Conflict, pp. 185-86). This practice of building on the New Testament pattern, listening to others, and sitting together to transact business remains the central purpose of every International General Assembly.

In many ways, the Assembly has moved well beyond what Spurling likely imagined on that August day in 1886. He had grown up in a Baptist system and no doubt envisioned the Christian Union as part of a network of congregations restoring the New Testament Church, which he believed had been lost when Christianity adopted creeds and human traditions. Indeed, the first General Assembly acted very much like an association of local churches with a congregational polity. Delegates were representatives of local congregations who discussed issues and made recommendations back to their churches for ratification.

In many ways, the Assembly has moved well beyond what Spurling likely imagined on that August day in 1886. He had grown up in a Baptist system and no doubt envisioned the Christian Union as part of a network of congregations restoring the New Testament Church, which he believed had been lost when Christianity adopted creeds and human traditions. Indeed, the first General Assembly acted very much like an association of local churches with a congregational polity. Delegates were representatives of local congregations who discussed issues and made recommendations back to their churches for ratification.

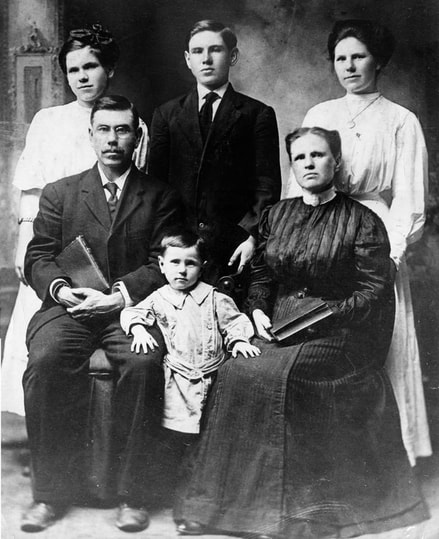

The A.J. Tomlinson Family about the time

The A.J. Tomlinson Family about the time he was first selected as general overseer

Christ Our Lawgiver

The most influential person in the development of Church of God government from the first Assembly forward was pastor, and later general overseer, A.J. Tomlinson. Tomlinson had grown up a Quaker and was influenced by radical holiness leaders such as Frank W. Sandford at the utopian community of Shiloh near Durham, Maine. Along with his leadership abilities and gifts, Tomlinson brought a vision of a restored apostolic church that would win the world to Christ in the last days.

When those who attended the 1896 Shearer Schoolhouse revival in Cherokee County, North Carolina, experienced sanctification, they were turned out of their Baptist churches. Consequently, they were wary of any church government. Yet, without government, they were susceptible to fanaticism and false doctrine. By 1902, W.F. Bryant and others were ready to heed the wise advice of R.G. Spurling to accept church government, and they organized the Holiness Church at Camp Creek.

Tomlinson saw a similar problem in the larger Pentecostal Movement following the revival at the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles. Many who had received a Spirit baptism experience found themselves excluded from their churches and denominations. Not surprisingly, they distrusted “organized” movements. Just as Spurling had encouraged the formation of a local congregation, Tomlinson believed that the entire Pentecostal Movement needed government based on the New Testament.

Writing to readers of The Evening Light and Church of God Evangel, Tomlinson concluded: “If all the Pentecostal people be in accord with Christ they will be in one accord with each other as a whole. What should the Pentecostal people do? Get in one accord with Christ in doctrine, and this will bring us all together in one body, into one organization, under one government, with only one law-giver, Christ, who is the Head of the Church. Jesus gave His Church for government, and all the laws for government come from Him through His Holy Apostles” (“Christ Our Law-Giver and King,” Nov. 1, 1910, pp. 1-2).

For Tomlinson, like the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15, the role of the General Assembly was to search the Scriptures in order to understand and apply Christ’s laws. Under Tomlinson’s leadership, there was no voting at the General Assembly. Rather, delegates searched the Bible for Christ’s laws and agreed together to apply those laws. Such practice was a process, and each General Assembly built upon the work of previous Assemblies believing that further study of the Scriptures might bring additional light on a matter. On occasion, the Assembly reviewed previous decisions and either affirmed or modified their earlier conclusions.

Tomlinson believed that with the additional light of each Assembly, the Church of God moved nearer to a restoration of the apostolic church. In 1913, he wrote, “The cries and groans for Apostolic methods, practices, and glory will be realized in the near future…. More light is showing, and revealing hidden treasures every year. Man’s ways and plans are fading from view. God’s ways and plans are being revealed” (Last Great Conflict, p. 132). With the full restoration of the apostolic church would come a global harvest such as the Church experienced on the Day of Pentecost when three thousand joined as a result of Peter’s sermon in Acts 2. Indeed, for Tomlinson, the days ahead were very bright for the Church of God.

The most influential person in the development of Church of God government from the first Assembly forward was pastor, and later general overseer, A.J. Tomlinson. Tomlinson had grown up a Quaker and was influenced by radical holiness leaders such as Frank W. Sandford at the utopian community of Shiloh near Durham, Maine. Along with his leadership abilities and gifts, Tomlinson brought a vision of a restored apostolic church that would win the world to Christ in the last days.

When those who attended the 1896 Shearer Schoolhouse revival in Cherokee County, North Carolina, experienced sanctification, they were turned out of their Baptist churches. Consequently, they were wary of any church government. Yet, without government, they were susceptible to fanaticism and false doctrine. By 1902, W.F. Bryant and others were ready to heed the wise advice of R.G. Spurling to accept church government, and they organized the Holiness Church at Camp Creek.

Tomlinson saw a similar problem in the larger Pentecostal Movement following the revival at the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles. Many who had received a Spirit baptism experience found themselves excluded from their churches and denominations. Not surprisingly, they distrusted “organized” movements. Just as Spurling had encouraged the formation of a local congregation, Tomlinson believed that the entire Pentecostal Movement needed government based on the New Testament.

Writing to readers of The Evening Light and Church of God Evangel, Tomlinson concluded: “If all the Pentecostal people be in accord with Christ they will be in one accord with each other as a whole. What should the Pentecostal people do? Get in one accord with Christ in doctrine, and this will bring us all together in one body, into one organization, under one government, with only one law-giver, Christ, who is the Head of the Church. Jesus gave His Church for government, and all the laws for government come from Him through His Holy Apostles” (“Christ Our Law-Giver and King,” Nov. 1, 1910, pp. 1-2).

For Tomlinson, like the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15, the role of the General Assembly was to search the Scriptures in order to understand and apply Christ’s laws. Under Tomlinson’s leadership, there was no voting at the General Assembly. Rather, delegates searched the Bible for Christ’s laws and agreed together to apply those laws. Such practice was a process, and each General Assembly built upon the work of previous Assemblies believing that further study of the Scriptures might bring additional light on a matter. On occasion, the Assembly reviewed previous decisions and either affirmed or modified their earlier conclusions.

Tomlinson believed that with the additional light of each Assembly, the Church of God moved nearer to a restoration of the apostolic church. In 1913, he wrote, “The cries and groans for Apostolic methods, practices, and glory will be realized in the near future…. More light is showing, and revealing hidden treasures every year. Man’s ways and plans are fading from view. God’s ways and plans are being revealed” (Last Great Conflict, p. 132). With the full restoration of the apostolic church would come a global harvest such as the Church experienced on the Day of Pentecost when three thousand joined as a result of Peter’s sermon in Acts 2. Indeed, for Tomlinson, the days ahead were very bright for the Church of God.

|

Developing Structure

Year by year the Assemblies developed structure as they saw it revealed in the New Testament. They created offices, governing bodies, committees, and a wide variety of ministries to build the Church and finish the Great Commission. General Overseer. Each of the first four General Assemblies chose a person to serve as moderator and clerk for the duration of the Assembly. But as God blessed the work, there was a growing need for coordination among the churches between Assemblies. Such coordination was especially desirable when supplying pastors because there were not yet enough for the established churches and missions. The fourth Assembly in 1909 concluded that a general moderator “was in harmony with New Testament order” and created that office to serve “over all the churches for mutual help and general instructions.” The duties of the office were: “To issue credentials to the ministers, to keep a record of all the preachers and evangelists within the bounds of the Assembly, to look after the general interests of the churches, to fill the vacancies either in person or by sending someone [who] in his best judgment would be beneficial to the edifying of the body of Christ, and to act as Moderator and Clerk of the General Assembly” (A. 1909, hand-written minutes, pp. 43-44). Additionally, delegates agreed to a term of one year from the close of one Assembly to the close of the next. They then chose A.J. Tomlinson as the first general moderator. The next Assembly in 1910 changed the title of this office to “general overseer.” Ninety years later, the 68th General Assembly in 2000 authorized the general overseer to use the title “presiding bishop.” Although the office of general moderator was a year-round position, it was not initially a full-time position. One week from the day the Assembly selected Tomlinson as general moderator in 1909, the Cleveland congregation chose him to continue to serve as their pastor. State Overseer. By the sixth Assembly in 1911, the Church had grown to fifty-eight congregations, 107 ministers, and 1,855 members in six states and one foreign country. General Overseer Tomlinson declared: “The work has grown to such a proportion now that there is a demand for a better system. As to just what should be done, and the form it should assume, I leave to the more able minds of this Assembly. The plans of the Bible should be sought out and followed, and yet much is left in which for us to exercise our own judgment.” The delegates considered appointing overseers for each state and concluded that this would be in “perfect harmony with the teachings of Scripture.” They immediately selected overseers for seven states and the Bahamas. The responsibilities of the newly appointed overseers were to give general oversight of their state, including an evangelistic campaign each year; to supply every church with a pastor; to keep records of all ministers and churches within the state, including the number of members in each church; and to provide a year-end report to the general overseer. In the early years, state overseers sometimes changed every year. Then in 1944, the General Assembly limited the state overseer’s tenure to four consecutive years in a state. This was later extended to 12 years with sufficient support of the state’s ministers. In 2000, the 68th Assembly gave state overseers the choice to use the title “administrative bishop,” which is now the custom of many state and regional overseers. Council of Eighteen. Each year Tomlinson presented an address to the delegates that introduced topics he believed the Assembly should consider in order to “put in motion the perfect New Testament order.” He first proposed the idea of an Elders Council in 1915. Calling attention to Acts 21:18, Tomlinson observed that James and an authoritative body of elders met together and formulated instructions for Paul. He petitioned, “As we are convened here to search for the apostolic order I appeal to my brethren for aid in deciphering such passages that we may be better able to perform our service, and more fully follow in the footsteps of those who operated the system of church building and evangelization so perfectly that every creature under heaven heard the gospel in their day” (A. 1915, p. 9). While discussing Acts 21, Tomlinson noted that “all” elders were present, that they convened for council and deliberation about matters dealing with the church, and that their gathering was private rather than public. For unrecorded reasons, the 1915 Assembly did not follow through on the subject of elders, so Tomlinson revived the issue the next year with a recommendation that the general overseer have a body “similar to the president’s cabinet.” He reiterated that just as James needed “assistance or counsel,” he too desired a deliberative body for such counsel. This time the delegates approved a plan to appoint elders to “have jurisdiction over all questions of every nature that may properly come before them, their actions and decisions to be ratified by the Assembly in session” (A. 1916, p. 28). By the end of their first meeting in October 1917, the elders had made 14 recommendations to the upcoming Assembly. International Executive Committee. As the Church of God continued to grow, the General Assembly created additional ministries. Often, Tomlinson recommended these ministries, and the Assembly responded positively to his leadership. Whether a recommendation came from the general overseer or from the General Assembly, Tomlinson frequently was asked to guide the ministry. The 1910 Assembly appointed a publishing committee to begin The Evening Light and Church of God Evangel, and Tomlinson became the editor of the new periodical. In 1911, Tomlinson recommended a preparatory school to train Christian workers, and the Assembly responded with the creation of an educational board naming Tomlinson as president. When the Bible Training School opened on January 1, 1918, Tomlinson served as superintendent. Among other responsibilities, Tomlinson edited Sunday school literature and gave oversight to building the Assembly Auditorium in 1920. The Assembly willingly placed him at the forefront of most of the Church’s activities, and he willingly led. He had a vision for the future of the Church, and the Church responded with enthusiasm. By 1922, many leaders and delegates recognized the necessity for additional general leadership, however. Increasing financial challenges accentuated this need, and the Assembly approved an “executive council,” comprised of the general overseer, a superintendent of education, and an editor and publisher to “council together on all matters of general interest to the Church of God and any and all departments…” (A. 1922, p. 49). The Assembly selected Tomlinson as general overseer, F.J. Lee as superintendent of education, and J.S. Llewellyn as editor and publisher. Now known as the International Executive Committee, this body oversees the ongoing ministries of the Church, and today includes the general overseer, three assistant general overseers, and a secretary general. International Executive Council. Although the Assembly approved an Elders Council in 1916, their relationship with the general overseer and the General Assembly remained somewhat ambiguous. With the creation of the Executive Committee in 1922, the Assembly agreed that these officers should meet with the Elders Council not less than once per year to “consider all the business affairs of the Church and give such counsel and advice as in their judgment they may deem necessary for the general welfare of the Church, and make such recommendations to the General Assembly as they may deem necessary” (A. 1922, p. 50). Currently, the International Executive Council meets three times a year and is comprised of the International Executive Committee and the Council of Eighteen, as well as the general moderator of the Full Gospel Church of God in Southern Africa. The general overseer of the Church of God in Indonesia also sits with the International Executive Council. Among their responsibilities, they give oversight to the general budget and recommend the agenda for the International General Council. International General Council. The second Assembly in 1907 included a “Preachers Conference.” At that meeting, the ministers adopted the name “Church of God” in the place of “Holiness Church,” which had been used by local congregations since 1903. Reflecting their desire to follow the New Testament pattern, they based this name on 1 Corinthians 1:2 and 2 Corinthians 1:1. Tomlinson later reflected in his book, The Last Great Conflict, that this decision “was not meant to debar the use of the other Scriptural names, such as: ‘The Church,’ ‘Churches in Christ,’ ‘Church….in God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ,’ etc.” (pp. 193-94). Then in 1929, the Assembly agreed to designate all bishops as elders, and to select the Elders Council from among all the bishops. Today, all ordained bishops registered and in attendance meet as the International General Council prior to the General Assembly. They elect the Council of Eighteen, nominate some offices to the International General Assembly, and set the agenda for the International General Assembly. |

COMMITTEES, DEPARTMENTS, & DIVISIONS

In 1909, the fourth Assembly appointed what appears to be the first General Assembly committee. A.J. Lawson, F.J. Lee, and P.A. Wingo were asked “to prepare a form for the annual reports of the Local churches” (A. 1909, hand-written minutes, p. 42). The committee reported to the Assembly the next day and their recommendation was adopted with a “slight amendment.” In 1910, the Assembly appointed a committee to prepare examination questions and Bible references for ministerial candidates. Their report led to the “Church Teachings,” which continue today as our Doctrinal Commitments. The Assembly also appointed a committee to discuss a Church paper, which led to the appointment of a publishing committee and the debut of The Evening Light and Church of God Evangel on March 1 of that year. Through the years, the Assembly, or denominational leaders the Assembly selected, has created ministries and departments as needed. To enhance already established ministries, the Assembly created standing boards for education, publishing, and missions in 1926. Most recently, the International General Assembly and denominational leadership have intentionally shifted the structure of Church of God general ministries from a departmental approach to a divisional approach. On many occasions, the Assembly has responded to a ministry vision presented to the delegates. In 1980, Lee College President Charles Conn, School of Theology President Cecil B. Knight, and General Overseer Ray H. Hughes joined together to present a plan for building a Pentecostal Resource Center. Their vision included a library to provide resources to students and a research facility to preserve our Pentecostal heritage. Not only did the Assembly approve the proposal, but also they gave financially to the vision. General Overseer Hughes reported: “When the program of the Pentecostal Resource Center was being presented, the Holy Spirit gripped the congregation in an extraordinary fashion. The people began to come forward and lay their gifts upon the pulpit, amidst the rejoicing and shouts of the congregation. This move of the Holy Spirit resulted in an offering of $200,000 toward the Pentecostal Resource Center. This sovereign act of the Holy Spirit brought healing to the body of Christ and the entire General Assembly was refreshed through an offering” (A. 1980, Preface). Church Historian Charles Conn penned in his journal, “It was one of the most marvelous breakthroughs of the Spirit I have seen. For more than an hour the people marched down and gave…” (Like a Mighty Army, 2008, p. 483). The funds given by the delegates resulted in construction of the building that today houses Squires Library and the Dixon Pentecostal Research Center. R.G. SPURLING ON CHURCH GOVERNMENT

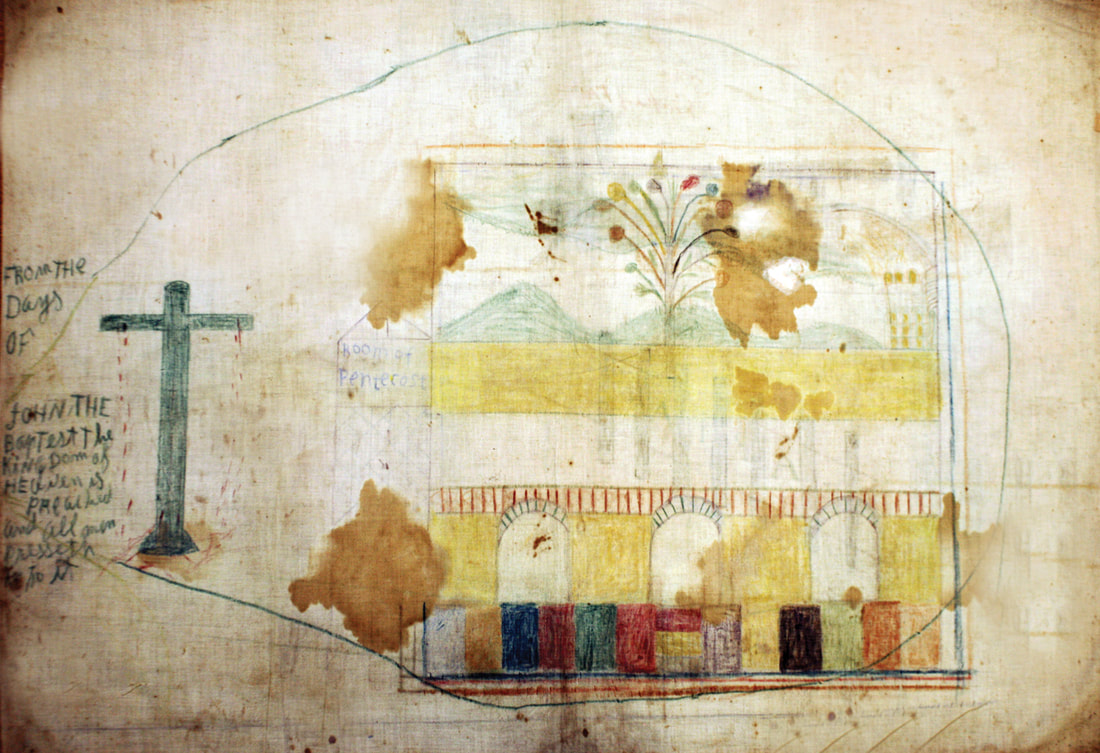

R.G. Spurling was a beloved “father in the faith” for our movement. At the eighth Assembly in January 1913, Spurling gave an address using an accompanying chart as a visual aid along with a song he had composed. He explained the development of the Church from its establishment at Pentecost, through centuries of human laws and creeds, to the current restoration of believers searching the Scriptures and seeking to be led by Jesus and governed by His laws. According to the Minutes, “After this was over brother Spurling sang the following verses amid shouts and cheers:

“Jesus our Lord from glory came

To make our minds and hearts the same; His gospel, law and government, Unto His children he has sent. “No more Gentile and the Jew, But one new man made of the two; The lines of strife no more to lay, But walk in love from day to day. “The law of love He did command, That by it we should understand; And by it all His children know, For out of it no strife can grow. “Alas! where is this law to-day, From which the Church is gone astray? The law of Christ we have denied, By human laws they are supplied. “Will you contrary to His will Be led by laws of human skill? Oh, then return unto His laws, And cease to build with wood and straws. “Oh, brethren for the sake of Christ, Leave off these laws that gender strife. Be by His Spirit ever led, He is the Church’s only head. “Following this song the power fell and all were on their feet with up-lifted hands, dancing and shouting the praises of God. One played the organ under the power of the Spirit. Then all who were not members and who had fallen in love with the Church and wished to become members were asked to stand up, and about twelve arose” (A. Jan. 1913, pp. 41-42). |

|

|

CENTRALIZED GOVERNMENT

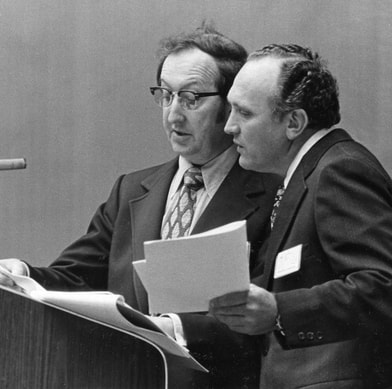

Long-time Parliamentarian R. Hollis Gause consults with General

Long-time Parliamentarian R. Hollis Gause consults with General Overseer Ray H. Hughes during the 1972 Assembly in Dallas.

Dr. Gause taught a course in parliamentary law at Lee College

and wrote Church of God Polity.

THROUGH ACTIONS of the General Assembly, the polity of the Church of God has moved from congregational practice to a centralized model. Acting within the context of Spurling’s Baptist roots, the first Assembly made recommendations for local churches to ratify. Tomlinson’s emphasis on the Jerusalem Council shifted Church of God polity toward what he identified as theocracy.

For Tomlinson, the General Assembly was that body through which the Church heard from God as the Spirit guided their search of the Scriptures. He considered this to be a rejection of episcopal polity and a recovery of the apostles’ government. Although the Church of God has bishops, our polity is not episcopal in the sense that bishops do not make final decisions. Rather, the Assembly, made up of ministers and laity, discerns God’s laws and directs bishops in the application of those laws. The role of the moderator, or presiding bishop, is to guide the Assembly and to discern the sense of the Assembly.

Our use of the term “centralized government” conveys the idea that local churches come together in the International General Assembly both to offer their gifts and to benefit from the cooperative ministries and protection of the whole body. In his Church of God Polity, long-time parliamentarian R. Hollis Gause wrote: “Basically the Church of God has a centralized government. This we believe to be Scriptural since the Jerusalem Council took the authority to render a decision affecting all the many local congregations (Acts 15). This was accepted by the apostles and was circulated among the churches.” He continued, “This centralization, however, is not of such intense character as to render local government weak and powerless. In order to preserve the values of both factors in government and to adhere to the principles of Scriptural government, the Church has several courts. These courts are as follows: local, district, state and territorial, and general (Church of God Polity, 1958, p. 11).

In his superbly subtle style, Gause established the role and meaning of “centralized government.” First, centralized government is based on the Scriptural account of the Jerusalem Council. Second, the Jerusalem Council, and by implication the General Assembly, has authority to make decisions affecting local churches. Third, the apostles, and by implication the clergy at all levels, accept and propagate the decisions of the Assembly. Fourth, the Assembly does not “lord over” local churches. Fifth, as a means of protecting the values and needs of both the Assembly and local churches, the Church of God has developed polity for local, district, state/regional, and general levels.

For Tomlinson, the General Assembly was that body through which the Church heard from God as the Spirit guided their search of the Scriptures. He considered this to be a rejection of episcopal polity and a recovery of the apostles’ government. Although the Church of God has bishops, our polity is not episcopal in the sense that bishops do not make final decisions. Rather, the Assembly, made up of ministers and laity, discerns God’s laws and directs bishops in the application of those laws. The role of the moderator, or presiding bishop, is to guide the Assembly and to discern the sense of the Assembly.

Our use of the term “centralized government” conveys the idea that local churches come together in the International General Assembly both to offer their gifts and to benefit from the cooperative ministries and protection of the whole body. In his Church of God Polity, long-time parliamentarian R. Hollis Gause wrote: “Basically the Church of God has a centralized government. This we believe to be Scriptural since the Jerusalem Council took the authority to render a decision affecting all the many local congregations (Acts 15). This was accepted by the apostles and was circulated among the churches.” He continued, “This centralization, however, is not of such intense character as to render local government weak and powerless. In order to preserve the values of both factors in government and to adhere to the principles of Scriptural government, the Church has several courts. These courts are as follows: local, district, state and territorial, and general (Church of God Polity, 1958, p. 11).

In his superbly subtle style, Gause established the role and meaning of “centralized government.” First, centralized government is based on the Scriptural account of the Jerusalem Council. Second, the Jerusalem Council, and by implication the General Assembly, has authority to make decisions affecting local churches. Third, the apostles, and by implication the clergy at all levels, accept and propagate the decisions of the Assembly. Fourth, the Assembly does not “lord over” local churches. Fifth, as a means of protecting the values and needs of both the Assembly and local churches, the Church of God has developed polity for local, district, state/regional, and general levels.

David G. Roebuck, Ph.D. is director of the Dixon Pentecostal Research Center, Church of God Historian,

and Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity at Lee University.

and Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity at Lee University.